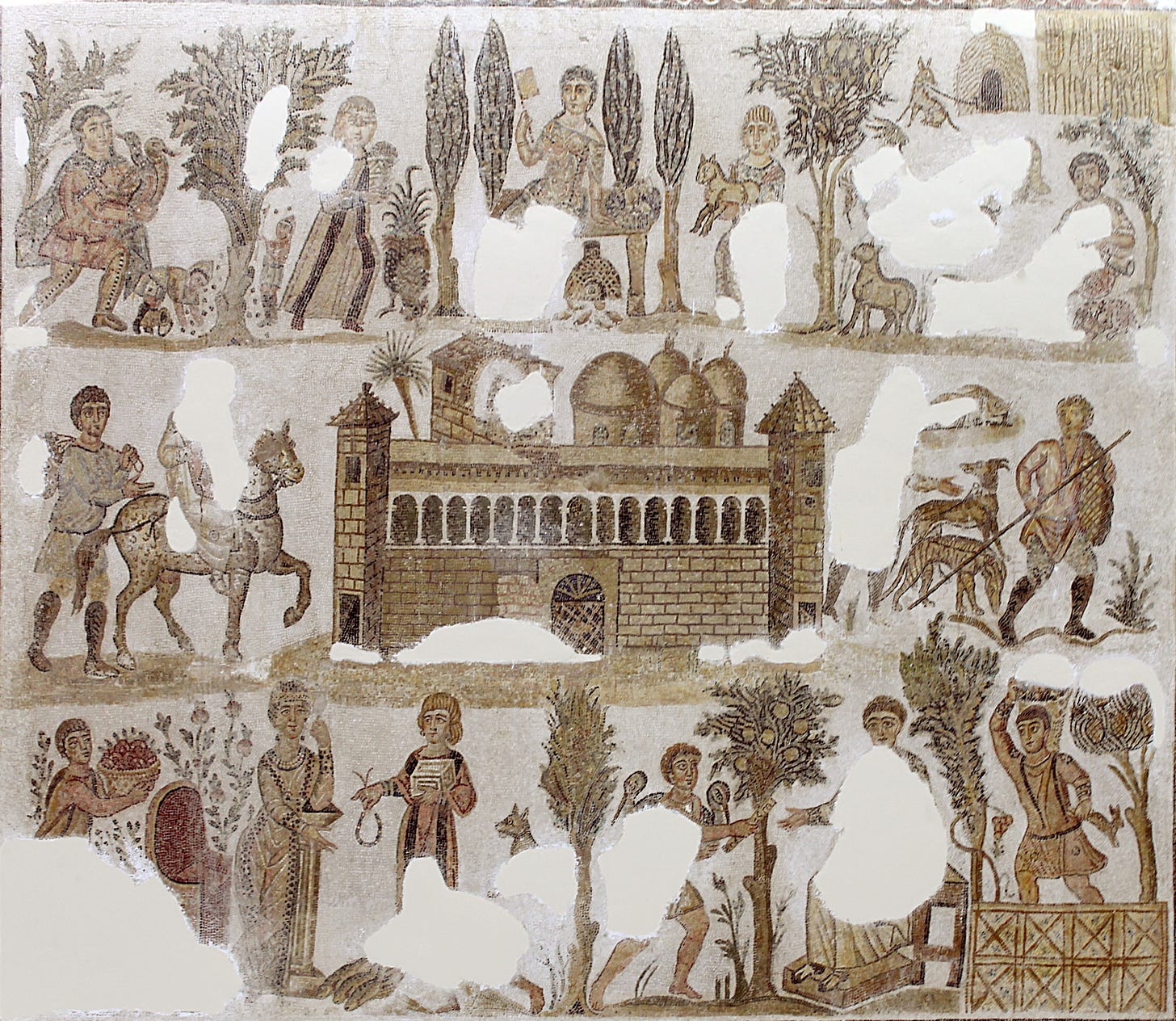

Mosaic of a latifundium from the house of Dominus Julius (4th-5th c. A.D.)

This entry of note-taking and synthesis of readings for the past few weeks encompasses research into the relationship between forms of slave labor and historical modes of production. At the outset, the distinction here is important, that slave labor persists across historical epochs and different modes of production, and thus prompts questions about the exact specificity of slave labor in the capitalist mode of production and this form of exploitation’s appearance in pre-capitalist modes of production. This project and my research interests at present are stated as a historiographic interpretation of the dynamics of class struggle in the longue durée of racial capitalism in the US, in order to chart out the relations and courses of development that link racial class formation, plantation slavery, and mass incarceration while also rejecting a reductive formulation of this trajectory. That said, establishing strong theoretical foundations at the outset is essential, especially given that the origins of the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade are essential to the origins of the capitalist mode of production, where the persistence of racialized slave labor in the formation and reproduction of modernity remains a matter of theoretical contention.

As debating the relation of the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade to the origins of the capitalist mode of production invites an investigation into research on the specificity of capitalist slavery, this specificity of capitalist slavery can only come into relief in its relation to slave labor’s prior historical iterations. Slave labor remains a historical constant from antiquity through modernity, though the generalization of the term tends to eclipse the various modes of practice of which distinct forms of slavery were constituted as a form of exploitation not unique to any determinate mode of production. This post and the next few to come will survey some studies on the subject from Marx, Perry Anderson, and Jairus Banaji on slave labor as a form of exploitation and its situation within socially and historically determinate relations of production, as well as preliminary notes on the role of slave labor in the formation of the capitalist mode of production. Informed by readings of Cedric Robinson and Fred Moten I will also explore its appearance as a substantive inequality that formed, in and through its racialized practices of subjugation and exploitation, the internally-constituted exteriority of primitive accumulation as a mediation of the formal equality that predicates abstract labor as the social substantialization of value, and the ongoing relational displacements constitutive of the form of surplus-value.

In his exposition of the value-form of the commodity that opens Capital, Marx develops the stage of his analysis of the equivalent form of the commodity, in which “the material commodity itself [...] expresses value just as it is in its everyday life, and is therefore endowed with the form of value by nature itself.”1 This is in contrast to the relative form of value, in which two commodities brought in relation to each other gain their appearance as values by that relation with the other commodity, an aspect of the same process of commodities brought in relation to each other as the exchange of commensurable products. Where the equivalent form is differentiated, as a moment of this process, is in the emergence here of the value-form of the product as both distinct moment of its existence and identity with its “natural”, or material, form as a use-value. It is in this exposition of these forms of value and their relation to the distillation of the value-form that Marx develops the category of abstract labor as that social form of labor that is unique to generalized commodity production:

“By equating, for example, the coat as a thing of value to the linen, we equate the labour embedded in the coat with the labour embedded in the linen. Now it is true that the tailoring which makes the coat is concrete labour of a different sort from the weaving which makes the linen. But the act of equating tailoring with weaving reduces the former in fact to what is really equal in the two kinds of labour, to the characteristic they have in common of being human labour. This is a roundabout way of saying that weaving too, in so far as it weaves value, has nothing to distinguish it from tailoring, and, consequently, is abstract human labour. It is only the expression of equivalence between different sorts of commodities which brings to view the specific character of value-creating labour, by actually reducing the different kinds of labour embedded in the different kinds of commodity to their common quality of being human labour in general.”2

We have here the formulation of a relation between labor and value distinct from and in critique of classical political economy’s labor theory of value, that that labor that produces value is of a specific character, and a feature of an economy where production is predominantly mediated and regulated by production under the imperatives of realizing exchange-value. Labor creates value only in so far as the social form of the commodity is the form of the product, and thus the formal presupposition of production the commodity, where all concrete labors are mediated through their generalization as human labor in the abstract. “Human labour-power in its fluid state, or human labour, creates value, but is not itself value.”3

The social form of human labor as abstract labor brings into relief the peculiarities that Marx addresses in the equivalent form of value as a development in the movement of the value-form from the relative form between commodities. First, in the equivalent form, “use-value becomes the form of appearance of its opposite, value.”4 Through this inversion by way of identification, “concrete labour becomes the form of manifestation of its opposite, abstract human labour.”5 What emerges then as a logical progression from this movement is that the “private labour [of the producer] takes the form of its opposite, namely labour in its directly social form.”6 Thus in the equivalence that is mediated between commodities in the value-form, the material existence of the commodity is simultaneous and identical to its existence as an abstract value, and all labors in turn appear as labor in its social form of abstract labor, regardless of its particular concrete task and the individuality of the producer in question. For Marx, this is the contradictory essence of the commodity-form, where value appears as a form that dominates content, and where the content of labor appears as both necessary to this form and also apart from and subordinate to it.

In the development of this exposition of the commodity as social form of product and production and its value-form, Marx takes an interesting moment to address the historical specificity of abstract labor and the value-form by way of Aristotle’s conception of justice in exchange, and the commensurability of objects in exchange. Where Aristotle is able to derive the simple form of value, of a commodity’s expression of value in relation to another commodity (the example given from Nicomachean Ethics is of 5 beds = 1 house), according to Marx, while Aristotle finds that these objects must be rendered qualitatively equal, and thus there no commensurability without equality, he cannot reconcile this with the impossibility, to his mind, of such unlike things being qualitatively equal. Thus he says of this inability to properly theorize the value-form:

“Aristotle therefore himself tells us what prevented any further analysis: the lack of a concept of value. What is the homogeneous element, i.e. the common substance, which the house represents from the point of view of the bed, in the value expression for the bed? Such a thing, in truth, cannot exist, says Aristotle. But why not? Towards the bed, the house represents something equal, in so far as it represents what is really equal, both in the bed and the house. And that is - human labour. However, Aristotle himself was unable to extract this fact, that in the form of commodity-values, all labour is expressed as equal human labour and therefore as labour of equal quality, by inspection from the form of value, because Greek society was founded on the labour of slaves, hence had as its natural basis the inequality of men and of their labour-powers. The secret of the expression of value, namely the equality and equivalence of all kinds of labour because and in so far as they are human labour in general, could not be deciphered until the concept of human equality had already acquired the permanence of a fixed popular opinion. This however becomes possible only in a society where the commodity-form is the universal form of the product of labour, hence the dominant social relation is the relation between men as possessors of commodities. Aristotle's genius is displayed precisely by his discovery of a relation of equality in the value-expression of commodities. Only the historical limitation inherent in the society in which he lived prevented him from finding out what 'in reality' this relation of equality consisted of.”7

This passage is not only interesting for that which it affirms of the historical specificity of the value-form and the social form of abstract labor, but for that which it offers us about the historically immanent operation of these elements of capitalist social relations prior to the capitalist mode of production, the political and juridical determinations of economic relations in the social constitution of form, and the function these play in the intelligibility of such social relations to the agents involved in their reproduction. Aspects of Aristotle’s conception of the simple form of value in Greek society is a piece of his conception of justice in exchange, where justice is not reducible to unqualified reciprocity in economy, but necessarily an equality in exchanges. In this, currency stands in as the mediator of qualitative difference, and a community for exchange requires this medium to render its concrete particularities intelligible, “[f]or no community [for exchange] is formed from two doctors. It is formed from a doctor and a farmer, and, in general, from people who are different and unequal and who must be equalized.”8 Here an early kernel of abstract labor appears present, yet it is still constrained by this economy of unequal labor in Grecian antiquity, where, for Aristotle, the measure of equalization carried out by currency “is need, which holds everything together; for if people needed nothing, or needed things to different extents, there would either be no exchange or not the same exchange. And currency has become a sort of pledge of need, by convention; in fact it has its name (nomisma) because it is not by nature, but by the current law (nomos), and it is within our power to alter it or make it useless.”9

Social relations of production are not only essential to the determination of consciousness in Marx’s formulation, but the social practices of historical agents are conscious actions in the constitution of their objective conditions of existence. The particularity of slave labor here in relation to Aristotle’s conception of currency, need, and the incommensurability of quality represents a form of economy where a determinate form of class rule and a conception of justice in exchange founded upon an inequality of labor, not only in terms of concrete task, but in formal Right, precludes the observance of the value-form as an autonomous object dominating production. Law is an intrinsic mode of economic articulation, as the fragmentation of the political, economic, and juridical characteristic of capitalist modernity requiring the theorization of their unified operation as modes of institutionalized class domination not yet extant in the light of the fetishism characteristic of commodity relations of production, where the fusion of need becomes identical to the realization of exchange-value and logic of surplus-value.

This aspect of slave labor’s condition as opposite to the formal equality characteristic of abstract labor as the social substance of commodity value in the capitalist mode of production presents us with a problem to explore, namely, the role of such labor deprived of formal equality in the reproduction of this condition of so-called free labor mediated by the wage-form. In order to do this, we may develop a comparative analysis of two accounts of slave labor in antiquity and its relation to capital from Perry Anderson and Jairus Banaji, for here there is too another problem: if there is still an emergent conception of abstract labor immanent to but occluded from generality by the social relations of modes of production in antiquity, how may we then understand the interrelation between capital as a dynamic historical category and capitalism as a historical mode of production? And further, how do we historicize capital as a dynamic social category, immanent to past modes of production, but not the dominant social relation of the production process until modernity? István Mészáros presents one of my favorite articulations of this, where he states:

“‘Capital’ is a dynamic historical category and the social force to which it corresponds appears — in the form of ‘monetary’, ‘mercantile’ etc. capital — many centuries before the social formation of capitalism as such emerges and consolidates itself. Indeed, Marx is very greatly concerned about grasping the historical specificities of the various forms of capital and their transitions into one another, until eventually industrial capital becomes the dominant force of the social/economic metabolism and objectively defines the classical phase of the capitalist formation.”10

This prompts us to observe the problematic of slave labor’s inequality as a possible form of the actuality of free (waged) labor’s formal equality in the general mediation of abstract labor in the monetary form of the wage, and these social relations in the totality of their operation as modes of existence of the commodity labor-power. To make this distinction, let us begin to look at an account of slave labor in antiquity. Perry Anderson’s Passages From Antiquity to Feudalism is a most useful compact volume for this history, though I should mention here that it is one that I have not uncritically adopted. Anderson relies, by his own admission, on secondary sources for his accounts of the social relations, production processes, and politico-juridical forms and operations of antiquity and early feudalism. While exploring his account here, I do not plan to take it as definitive. Likewise, Jairus Banaji raises an important and brusque critique of the text in one of the essays of his work Theory As History, where he takes Anderson to task for his overly-simplistic use of Marxist categories, and his identification of the mode of production of with a form of exploitation with his assignment of “the slave mode of production” as the dominant mode of production of Greece, the Hellenistic world, and the Roman Empire. These problems of Banaji’s will be returned to below.

What remains of interest to us here, however, despite Anderson’s demonstrable theoretical errors, are the operations of slave labor that he draws attention to and that can in turn bring into relief that which is specific to capitalist slavery, while also that which is inherited by it from these pre-capitalist social relations as those modes of practice in the process of production and reproduction of material life immanently-positing of capital. Thus our present concern is this relationship of coterminous equality and its absence that conditions and articulates conceptions of liberty across historical forms of class society, and the reproduction of such relations in the mode of production, establishing a sense of historical continuity-in-disjunction, social and historical intelligibility across epochs of qualitatively distinct historical modes of production. Anderson’s unity-of-opposites where “Hellenic liberty and slavery were indivisible: each was the structural condition of the other” forms the “ condition of possibility of this metropolitan grandeur in the absence of municipal industry was the existence of slave-labour in the countryside: for it alone could free a landowning class so radically from its rural background that it could be transmuted into an essentially urban citizenry that yet still drew its fundamental wealth from the soil.”11 The bridge between Greek to Roman administrations of slave labor finds its articulation in this conception of relations of production and the labor market for the enslaved Anderson offers us here:

“On the one hand, slavery represented the most radical rural degradation of labour imaginable - the conversion of men themselves into inert means of production by their deprivation of every social right and their legal assimilation to beasts of burden: in Roman theory, the agricultural slave was designated an instrumentum vocale, the speaking tool, one grade away from the livestock that constituted an instrumentum semi-vocale, and two from the implement which was an instrumenturn mutum. On the other hand, slavery was simultaneously the most drastic urban commercialization of labour conceivable: the reduction of the total person of the labourer to a standard object of sale and purchase, in metropolitan markets of commodity exchange. The destination of the numerical bulk of slaves in classical Antiquity was agrarian labour (this was not so everywhere or always, but was in aggregate the case): their normal assemblage, allocation and dispatch was effected from the marts of the cities, where many of them were also, of course, employed. Slavery was thus the economic hinge that joined town and country together, to the inordinate profit of the polis.”12

Thus we have here a conception of the trade economies of antiquity, in the Eastern regions of the Mediterranean and the Aegean, where commodity circulation proliferated, even with the commodification of labor (and by logical extension, some form of labor-power), but with the prevalence of slave labor as the form of exploitation predominant in the region. The slave estate form of production of antiquity developed an agrarian economy that saw a division of town and country in accordance with an inter-class stratification of slave and urban artisan working classes. The emergence of capital in circulation, as Marx locates it in reference to mercantile wealth in the manuscripts published as the third volume of Capital,13 develops from here in the specific manner in which the polis political apparatus and inter-regional trade economy formed an immanent commodity economy and thus, intelligible to us from our vantage point, a form of underdeveloped command of surplus labor.

This relation between forms of slavery, surplus labor, and surplus value will be important to develop in moving forward, as this command of surplus labor in a manner consistent with the self-expanding movement of the production process as valorization process is essential to the capitalist mode of production, and we are here looking for its seeds in these partial excavations of the past. A distinction here that is relevant is the dynamic of surplus labor’s exploitation, and a clear distinction is the relative fixity of productivity that Anderson identifies between the capitalist mode of production and the modes of command in the sites of slave labor in Mediterranean antiquity:

“Productivity was fixed by the perennial routine of the instrumentum vocalis, which devalued all labour by precluding any sustained concern with devices to save it. The typical path of expansion in Antiquity, for any given state, was thus always a ‘lateral’ one - geographical conquest - not economic advance. Classical civilization was in consequence inherently colonial in character: the cellular citystate invariably reproduced itself, in phases of ascent, by settlement and war. Plunder, tribute and slaves were the central objects of aggrandisement, both means and ends to colonial expansion. Military power was more closely locked to economic growth than in perhaps any other mode of production, before or since, because the main single origin of slave-labour was normally captured prisoners of war, while the raising of free urban troops for war depended on the maintenance of production at home by slaves; battle-fields provided the manpower for cornfields, and vice-versa, captive labourers permitted the creation of citizen armies.”14

This tie in the accumulation of slave labor to conquest is essential in Anderson’s conception of the dynamics of the production process of the Roman republic, and subsequently its imperial trajectory, as a form of perpetual conquest bound up with its own internal reproduction and systems of tribute and taxation, though it is important here to remember Marx’s warning of such a focus on plunder contra Bastiat, for “if people live by plunder for centuries there must, after all, always be something there to plunder; in other words, the objects of plunder must be continually reproduced. It seems, therefore, that even the Greeks and the Romans had a process of production, hence an economy, which constituted the material basis of their world as much as the bourgeois economy constitutes that of the present-day world.”15 Anderson certainly does not make this relation clear, as his conception of social reproduction in the predominant modes of production in Greek and Roman society (though most predominantly the latter) finds the procurement of slave labor through conquest and the open arable land expansion in the Western regions of the European continent the primary reasons for the Roman Empire’s relative sustainability, but also the internal dynamics of its eventual historical transience.

We will pick up this thread letter in the next post with a more thorough engagement of the problems of Anderson’s conception of slave labor and modes of production through the work of Jairus Banaji.

Marx, Karl. 1990. Capital: A Critique of Political Economy Vol. 1. Harmondsworth: Penguin In Association With New Left Review. P. 149

Ibid, p. 142, emphasis mine.

Ibid, p. 142, emphasis mine.

Ibid, p. 148

Ibid, p. 150

Ibid, p. 151

Ibid, pp. 151-2, emphasis mine.

Aristotle, trans. Terence Irwin. 2006. Nicomachean Ethics. Indianapolis, IN: Hackett. P. 75

Ibid.

István Mészáros. 1995. Beyond Capital : Toward a Theory of Transition. London: Merlin Press ; New York. p. 938

Anderson, Perry. 1975. Passages from Antiquity to Feudalism. London: Verso. Pp. 23-4

Ibid, pp. 24-5

“Here the product becomes a commodity through trade. It is trade that shapes the products into commodities; not the produced commodities whose movements constitutes trade. Capital as capital, therefore, appears first of all in the circulation process.” Marx, Karl, and David Fernbach. 1991. Capital: A Critique of Political Economy. Vol. 3. London Penguin Books In Association With New Left Review. P. 445

Anderson 1975 p. 28

Marx 1990 p. 175

Eagerly awaiting the next instalment! This was super good